-

![]() WSET® Certification

WSET® Certification -

![]() Choice of classroom and/or online

Choice of classroom and/or online -

![]() Personalised approach

Personalised approach -

![]() LifeLong Learning

LifeLong Learning -

![]() Also in your company

Also in your company

Ahead of the Australian wine masterclass and free-pour tasting in Gent on 3 June, we chat to Wine Australia’s Emma Symington MW.

Emma Symington MW has worked in the wine trade for nearly 20 years with previous roles including selling and buying wine. She is Wine Australia’s Head of Education for the UK and Europe, organising and hosting tastings, seminars and masterclasses to increase enthusiasm and knowledge in Australia’s wines and wine regions.

You have been with Wine Australia for over ten years, what excites you about Australian wine and are you still making discoveries?

You have been with Wine Australia for over ten years, what excites you about Australian wine and are you still making discoveries?

I’ve worked for Wine Australia for 13 years, and in that time have visited multiple regions in Australia, talked to many winemakers and viticulturists and tasted countless wines – but there’s still so much to explore. With 65 distinct regions and more than 150 grape varieties planted from Assyrtiko to Zweigelt, there’s always something new to discover. Without laws restricting what can be planted and where, Australian producers are an eclectic and innovative bunch. They’re always looking to improve and not afraid to try new things – and while they respect tradition, they’re never beholden to it. That’s what makes Australian wine so exciting.

On my last trip in November 2024 the focus on site and vineyards was clear to see – be it with classics such as Hunter Valley Semillon and Barossa Valley Shiraz, or with new wave styles like McLaren Vale Grenache or Adelaide Hills Grüner Veltliner. With much of Australia being phylloxera-free, vine and vineyard health is integral and keeping this status is hugely important – particularly when you realise some of the oldest vines in the world are in Australia.

We’ll discuss more about Australia’s old vines and classic styles in the masterclass and you’ll be able to try new wave styles and alternative varieties like Chenin Blanc, Marsanne and Touriga Nacional in the free-pour tasting.

Chardonnay from regions like Margaret River and Yarra Valley now rival the best in the world. What techniques are Australian winemakers using to achieve elegance and complexity?

Australian Chardonnay made a name for itself on rich, oaky styles of wine, full of flavour and ripe fruit. But there’s now a new wave of fresh, elegant and regionally-distinct Australian Chardonnay. The quest for finesse and freshness has led producers to cool-climate sites and encouraged winemakers to experiment with different methods.

Cool climate regions include Tasmania, Western Australia (Great Southern, Geographe), Victoria (Yarra Valley, Gippsland, Mornington Peninsula), South Australia (Adelaide Hills) and NSW (Canberra District, Orange, Tumbarumba). Techniques in the vineyard and winery have evolved: hand harvesting, earlier picking, more gentle use of oak and the move to older and larger format French oak, minimal intervention and wild ferments are some of the practices that are reshaping the face of Chardonnay. Guests will be able to taste Chardonnay from iconic wineries, innovative producers and cool climate regions in the masterclass.

The line-up includes a Chardonnay from the Anvers estate vineyard in Adelaide Hills. It is named Anvers because the winery owners Wayne and Myriam Keoghan met each other there in Belgium.

You can learn more about Chardonnay in our Australian Wine Discovered guide on https://www.wineaustralia.com/education/chardonnay.

Australian Shiraz has evolved dramatically – from bold, high-alcohol styles to more refined, site-specific expressions. How do you define modern Australian Shiraz?

Australian Shiraz comes in many forms – from bold BBQ reds to iconic, elegant fine wines. Warm climates usually produce full-bodied, richly flavoured and textured wines, while cooler climates generally make medium-bodied and spicy styles. From rogue to refined, classic to contemporary, there’s a style of Aussie Shiraz for everyone. Modern Australian Shiraz is all about diversity.

Some of the most elegant and perfumed styles of Shiraz are from regions with cool nights and high diurnal temperature ranges. Often with less oak, these fresh approachable styles are sometimes labelled Syrah – for example the Ochota Barrels ‘Where’s The Pope’ McLaren Vale Syrah, which we’ll be showing in the masterclass.

You can learn more about Shiraz in our Australian Wine Discovered guide on https://www.wineaustralia.com/education/shiraz-and-blends.

Sustainability is a major selling point in Belgium. What are Wine Australia and Australian producers doing in this space?

Sustainability is important across the sector and Wine Australia is working together with the Australian Wine Research Institute and Australian Grape & Wine to run the national programme, Sustainable Winegrowing Australia, which measures and reports sustainable practices as well as encouraging best practice in vineyards and wineries.

Australian producers are always seeking new ways to improve sustainability in the vineyard and winery, from introducing goats and cover crops, installing soil moisture sensors and solar panels, and using lightweight bottles and alternative packaging. You can find out more about Sustainable Winegrowing Australia, read case studies from producers, and download the Impact Report from https://sustainablewinegrowing.com.au/.

By sharing the Impact Report, encouraging wineries to display the Sustainable Winegrowing Australia trust mark on bottles, and listing certified wineries at our events, this enables retailers and consumers to identify sustainably made wine and helps people to do their bit for the planet.

Are you working in the Horeca or Wine trade then you can subscribe for free for one of the Masterclasses. Other students are welcome for the free pour tasting.

Download here the list of the available wines.

Subscribe here: WINE AUSTRALIA – 3/06/25 – GENT

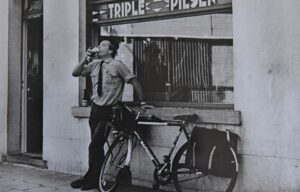

In all your wine enthusiasm, you probably lost sight of the fact that Belgium is the ultimate beer country. After water and tea, beer is the most consumed beverage in the world. And our little triangle on the North Sea is the foaming and bubbling epicentre.

Our country has a reputation to uphold. Belgian beer is celebrated far and wide, across every corner of the six continents. Belgium is considered to be the ‘beer paradise’ by beer lovers. Ask any tourist about the typical characteristics of Belgium, and you will hear about Bruges, our refined chocolate, the Red Devils or more recently Nafi Thiam and Remco 🙂 and of course: our beer. But is there really such a thing as ‘Belgian beer’? And can Belgium really claim the predicate ‘world’s best beer country’? Yes, however, the answer is more nuanced than that. To truly understand Belgian beer culture, we need to consider various geographical, historical, religious, political, and legal aspects.

The beer belt

Belgium belongs to the so-called ‘beer belt’, a wide strip that crosses Europe from east to west. Our country has the necessary raw materials, such as barley and hops, to produce beer. Moreover, some regions are renowned for their excellent water quality. For instance, Spa has become a household name in the world of mineral water and wellness centers, thanks to the famous springs in the Walloon town of Spa.

Over the centuries, Belgium has been constantly occupied by various foreign powers: Romans, Franks, French, Spanish, Austrians, Germans… and yes, even the ‘Dutch’ have held sway in our regions. Our reaction to this was twofold: on the one hand, we adopted the good elements and integrated these influences into our (beer) culture. On the other hand, we stubbornly stuck to our (beer) traditions to preserve our individuality. Some historians even see beer drinking as a form of resistance, though we prefer not to take that idea too far..

Trappist beer

Six of the ten Trappist breweries (Achel, Chimay, Orval, Rochefort, Westmalle, and Westvleteren) are located on Belgian soil. This is no coincidence. Catholic Belgium served for centuries as a safe haven for religious communities persecuted in their home countries. Our northern (Netherlands) and eastern neighbors (Germany) embraced Protestantism, while in turbulent France, the church was often the target of criticism. Many monks found a second home in our regions. Since beer was the quintessential drink of the people, these newcomers dedicated themselves to the craft of brewing—to our great delight. Incidentally, the two Dutch Trappist breweries are just a stone’s throw from the Belgian border.

Six of the ten Trappist breweries (Achel, Chimay, Orval, Rochefort, Westmalle, and Westvleteren) are located on Belgian soil. This is no coincidence. Catholic Belgium served for centuries as a safe haven for religious communities persecuted in their home countries. Our northern (Netherlands) and eastern neighbors (Germany) embraced Protestantism, while in turbulent France, the church was often the target of criticism. Many monks found a second home in our regions. Since beer was the quintessential drink of the people, these newcomers dedicated themselves to the craft of brewing—to our great delight. Incidentally, the two Dutch Trappist breweries are just a stone’s throw from the Belgian border.

The Influence of Politics and Legislation

As always, politics played a role. Every village of any size had at least two breweries: one with a Catholic signature and one with a liberal or socialist background. Treating ‘pints’ proved a powerful weapon in election campaigns. In many cases, the brewer was also the mayor. A good tradition, if you ask me-fresh, hoppy beer rather than political messages that sour.

From politics to government intervention is usually just a small step. The Vandervelde Act of 1919 banned the serving of liquor in pubs. This law was introduced in response to the dire situation at the time: workers were paid off after a long working week at the local pub, often owned by the patron. Tired men with money in their pockets in a pub full of friends formed an explosive cocktail. The result: drunken men who returned home penniless, abused their wives, and plunged their families into misery. The law was supposed to address this situation and curb alcoholism among the impoverished population.

Brewers saw their opportunity and launched beers with higher alcohol volume. Some great classics, such as Duvel, Westmalle Tripel, and Bush by Dubuisson, saw the light of day during this period. Although the Vandervelde Act ultimately turned out to be a slap in the face, we still owe some excellent beers to this government intervention.

Belgian Brewers: Freedom and Creativity

Compared to their German and English counterparts, our brewers enjoyed relatively more freedom. German brewers were confined by the strictures of the Reinheitsgebot (which allowed only hops, water, malt, and yeast). This law was only partially repealed in 1987 under pressure from the EU. English brewers groaned under the weight of high alcohol taxes. Starting in 1880, Prime Minister Gladstone based these taxes on the strength of the beer rather than the malt content. The result was that low-alcohol beers became dominant in the English beer landscape.

Combine all these elements, and the foundation is laid for a thriving beer culture. Colors, aromas, flavors—Belgium can boast an enormous variety of beers, born from the ‘savoir-faire,’ passion, and unceasing creativity of our brewers. Thanks to our rich history, beer reigns supreme in Belgium.

WineWise recently started offering the brand new WSET Beer training courses. To guarantee the quality of the content, we work together with beer specialist Luc De Raedemaeker. He joined our WineWise Trainers team and will teach the beer courses.

Discover for yourself the rich world of beer and become a real beer expert!

Register for the WineWise WSET beer training course and learn all about the unique flavours, styles and traditions of beer.

If you’d ask which wine regions in the world are currently most undervalued, Jerez is definitely in my top five. Sherries are not your average quaffable or ‘easy’ wines, and their reputation as a Sunday aperitif for well-coiffed grannies unfortunately lingers. Yet there is so much more to sherry than the weeks-old, basic-quality finos we learnt to avoid in many pubs and restaurants.

Anno 2023, Jerez’ producers are increasingly focusing on quality rather than quantity, and we get to discover an exciting diversity of styles and opportunities to explore their food-pairing potential.

Copa Jerez 2023

The versatility and food-friendliness of sherry wines were confirmed once more a few weeks ago, in what has become the heyday of sherry-focused gastronomy: the Copa Jerez. After Fabian Bail and Paul-Henri Cuvelier of restaurant Paul de Pierre took home the three main prizes in 2021 (Best Chef, Best Sommelier and Best Pairings overall), I can only imagine the courage it must have taken to register for this year’s Belgian preselection. But fortunately those brave souls did show up, and among them, Chef Arnout Desmedt and Sommelier Gianluca Di Taranto of A Cook & GDT were selected to represent Belgium for the 20th anniversary edition of the Copa Jerez.

2021 met de drie hoofdprijzen naar huis kwamen (Beste Chef, Beste Sommelier and Beste Pairings), kan ik me voorstellen dat het veel moed vergde van de nieuwe lichting om zich in te schrijven voor de Belgische preselectie van dit jaar. Maar gelukkig durfden verschillende dapperen het aan, en onder hen werden Chef Arnout Desmedt en Sommelier Gianluca Di Taranto van A Cook & GDT geselecteerd om België te vertegenwoordigen op de 20ste editie van de Copa Jerez. De magie die we proefden bij de Belgische finale, hebben ze in Jerez ook kunnen overbrengen aan de indrukwekkende vijfkoppige jury, met Jancis Robinson (Master of Wine & wijn journalist), Almudena Alberca (Master of Wine & wijnmaker), Melania Bellesini (sommelier van The Fat Duck***), Pascaline Lepeltier (schrijfster & Beste Sommelier van Frankrijk 2018) en Josep Roca (sommelier & mede-eigenaar van El Celler de Can Roca***).

They worked their magic in Jerez too, resenting stunning dishes and pairings, which landed them a second place overall, and as the cherry on top, Gianluca won the coveted ‘Juli Soler Award for Best Sommelier’ award. The impressive five-member jury was Jancis Robinson (Master of Wine, wine writer and critic), Almudena Alberca (Master of Wine and winemaker), Melania Bellesini (sommelier at The Fat Duck***), Pascaline Lepeltier (writer and Best Sommelier in France 2018) and Josep Roca (sommelier and co-owner of El Celler de Can Roca***).

Their artichokes starter, paired with Bodegas Valdespino’s Fino Inocente, was inspired; followed by a gutsy plant-based main course, titled ‘winter vegetable rice’, matched with Equipo Navazos’ scrumptious Manzanilla Pasada La Bota 103. To end with a playful take on Crêpe Suzette (without the crêpe, with Cox apples ánd served in an orange), which they served with the excellent Cream Tradición VOS by Bodegas Tradición.

Jerez – blending old and new

To develop a deeper understanding of any wine region, its people and its products, you need not only savour the local food and drinks, but also walk the vineyards, sniff the air, feel the soils under your feet and the weather conditions on your skin. Fortunately this trip also offered the opportunity to do just that.

Seeing the grey-green dust-covered vines helped me understand why clarifying the must before fermentation is essential here. Hearing and feeling the albariza soils crunch under my feet, baked to a crust by relentless sunshine, gave clues about how vines survive the dry summers here, but also why aserpia troughs are dug between the vine rows after harvest to make the most of the autumn and winter rains.

Seeing the grey-green dust-covered vines helped me understand why clarifying the must before fermentation is essential here. Hearing and feeling the albariza soils crunch under my feet, baked to a crust by relentless sunshine, gave clues about how vines survive the dry summers here, but also why aserpia troughs are dug between the vine rows after harvest to make the most of the autumn and winter rains.

Equally, strolling between the endless rows of casks in the cathedral-like bodegas, soaking up the bordering-on-spiritual atmosphere, permeated with yeasty, nutty, curry-like smells and misty cellar dust, made it sink in what a unique heritage is being preserved here.

And Jerez is evolving, with an increasing number of quality-focused producers, and interesting developments in the production of unfortified wines.

Unfortified wines as such are not a new phenomenon in Jerez; they are part of the region’s history. Traditionally there were the so-called ‘vinos de pasto’ or ‘wines of the grasslands’, referring to the typical food wines of the region, intended for local consumption. There also are many historic references to unfortified sherry-like wines, which achieved a high alcohol percentage due to late harvesting and/or the soleo or asoleo process of sun-drying the grapes, before fortifying became more popular in the 17th and 18th centuries to stabilise the wines for their long sea voyages to foreign markets. In D.O. Montilla-Moriles, creating sherry-like wines without fortification is still common, and if you haven’t tried an unfortified Fino from PX grapes yet, I highly recommend it.

Closer to Jerez, unfortified sherries have also been gaining traction these past 15 years, and this is reflected in the new regulations for the D.O. Jerez. Since October 2022, sherry wines no longer have to be fortified, providing they reach the minimum required alcohol percentage (15% for Fino and Manzanilla). The other rules, i.a. undergoing biological ageing under flor and maturation for a minimum of two years, of course still apply.

Interesting to note also is that in those new regulations, a number of traditional grape varieties such as Beba, Perruno and Vigiriega, have been included for sherry production, and the Zona de Crianza or area of maturation has been expanded to match the area of production. This means that sherry wines now no longer have to be matured in the ‘Sherry Triangle’ of Jerez de la Frontera, El Puerto de Santa María and Sanlúcar de Barrameda. Bodegas in surrounding towns, such as Chipiona and Chiclana, can now mature, market and sell their own sherries directly as D.O. Jerez.

These are interesting developments for sure, but how it will play out is impossible to predict at this stage. One thing is certain: the Consejo Regulador and the sherry producers will have their work cut out for them: guiding sherry into a new era, navigating new and changing markets and consumer preferences, exploring the food-pairing potential of the different sherry styles with diverse cuisines from all over the globe, and all this while raising and upholding quality standards. And they will need to come up with a fitting name for the increasingly popular ‘regular’, unfortified wines category in Jerez, which has much higher quality ambitions and gastronomic potential than its current, unofficial name tag ‘vino de pasto’ indicates. If you’d have any suggestions, do let them know …

Meanwhile, as the days turn cold and dark again, few comforts are more soothing to the soul than curling up on the sofa with a glass of your favourite sherry in hand.

Meanwhile, as the days turn cold and dark again, few comforts are more soothing to the soul than curling up on the sofa with a glass of your favourite sherry in hand.

Salud, to a great autumn and a heart- and belly-warming winter!

For the final section of the paper, WSET wanted us to look at the relationship consumers have with sustainability: does sustainability benefit the consumer, and to what extent does it influence their behaviour?

Does sustainability benefit the consumer?

True sustainability certainly should benefit consumers, as it balances the interests of people, planet and profit. It affects the air each of us breathes; the water – and wine – we drink; the life we live and the resources available to live it, for us as well as our descendants.

Economic growth has brought many benefits, from reducing poverty to improving human rights and access to education, healthcare, water and sanitation. However, what London-based sustainability researchers Paul Ekins & Dimitri Zenghelis call the ‘grow now, clean up later’ mindset, has long ignored externalities. As they put it rather dramatically: ‘this approach has brought human societies to the brink of catastrophe, putting at serious risk all these benefits and, indeed, the continuance of human civilisation itself’.

We can safely assume that measures that allow us to continue human civilisation, business, trade and food and wine production, benefit consumers in the long run. In the short term, however, prices may go up to reflect the full cost of a product. To be economically sustainable, pricing needs to include those expenses that were previously passed on to other parties or future generations. Although price increases may not feel like a benefit to consumers, fair pricing provides the basis for continued, sustainable production and consumption.

Another – less obvious – benefit is that sustainability success stories give us hope. In these times of negative news, improvements in environmental, social and economic indicators motivate us to go on. One of my favourite scientists in our solar system, professor Hans Rosling, called this ‘factfulness: understanding as a source of mental peace’. He warned against losing hope: ‘when people wrongly believe that nothing is improving, they may conclude that nothing we have tried so far is working and lose confidence in measures that actually work.’

Does sustainability influence consumer behaviour?

Research by consumer research organisation Wine Intelligence reveals that wine consumers care about personalisation, experience, convenience and sustainability. Sustainably produced wines align with ‘ethical consumerism’ and consumers perceive them as innovative, trendy, and offering health benefits.

However, consumption behaviour is not entirely consistent with these positive associations; a phenomenon known as the green attitude-behaviour gap or green purchasing inconsistency. According to White et al.: ‘a frustrating paradox remains at the heart of green business: few consumers who report positive attitudes toward eco-friendly products and services follow through with their wallets’.

In one of the Institute of Masters of Wine’s seminars, wine researcher Juan Park explains this by how our brain uses innate pain and reward systems for purchasing decisions. When consumers consider a purchase, their brain weighs what they get out of it, against what it will cost them. If the perceived rewards outweigh the pain, they are likely to buy. Among wine consumers queried by Wine Intelligence, 55% worry about climate. Yet only 40% were willing to endure more ‘pain’ for sustainable wines, in the form of paying more or giving up convenience. However, when a product aligned with their self-image and beliefs, or it was associated with higher standards and quality (= higher rewards), consumers were more likely to buy. Wine label terms such as ‘natural wine’, ‘organic’, ‘environmentally-friendly’, ‘sustainably-produced’, ‘preservative-free’ or ‘fair-trade’ increased consumers’ willingness to buy; while claims which confused them, such as ‘sulphite-free’, ‘carbon-neutral’, ‘biodynamic’, ‘vegan’ or ‘vegetarian’, had the opposite effect.

All this suggests consumers care about and are influenced by sustainability, providing they understand the rewards. An Italian study confirmed that responses to sustainability claims are heterogenous, but overall, labels addressing environmental aspects increase sales. In addition, consumers are willing to pay a premium for wines produced by companies that respect fair working conditions.

Positive effects of sustainability on consumption behaviour are demonstrated across consumer segments, and most of all with millennials, provided sustainability claims are well defined and prominently displayed. A recent study among South-African consumers showed that especially younger individuals with higher incomes, higher education levels and better knowledge of eco-certification were willing to pay a higher price for sustainably produced and fair-trade wines. For low-income consumers, however, higher prices form a barrier, irrespective of their attitudes towards environmentalism.

To summarise and conclude…

When wine businesses want to improve their environmental, social or economic sustainability, it is essential they make an in-depth analysis of the current situation, which highlights where gains can be achieved. In decisions to lower a winery’s environmental impact, the full lifecycle of technologies and measures should be considered. Furthermore, by raising awareness, improving working conditions and involving employees in all sections of the winery, more hands and minds will be working towards achieving the sustainability objectives. And finally, marketing and communication matter. Clear and prominently conveyed sustainability efforts increase a wine’s attractiveness to consumers, boost employee engagement and strengthen the overall brand image and impact. Spread the word to your customers!

Thank you Kristel !

This article is based on the July 2022 D6 paper Kristel Balcaen DipWSET submitted. Read it here.

Kristel passed this paper with distinction, a mark that few achieve for this unit within the WSET Diploma course.

In July’s D6 paper, we were also asked to examine how wine producers can improve their social sustainability through employee relationships. Another interesting angle to truly sustainable development, and one we may not automatically consider when we hear the word ‘sustainability’.

Social sustainability deals with the identification and management of business impacts on people, both positive and negative. What companies do, directly or indirectly affects their employees, workers in the wider value chain, their customers and the local community they are embedded in.

How to improve social sustainability for wine industry employees is a complicated question, in part because social sustainability has many faces. Wine is produced on all continents but Antarctica, and circumstances in different countries, regions and layers of society are highly divergent. In areas with stable, mature economies and reliable social protection in place, the focus tends to be on wellbeing, actions to improve work-life balance and on mitigating the effects of peak-season overtime. Meanwhile, in regions where working conditions for full-time, seasonal or migrant workers are still largely unregulated, sustainability needs to address basic human rights, health and safety first.

Working conditions and workers’ rights

Working conditions and workers’ rights

To illustrate this chasm: a 2020 study in Austria and Germany identified job satisfaction criteria among wine sector employees, such as remuneration, career opportunities, recognition by colleagues and managers, quality of the wines and alignment with the company’s philosophy.

In contrast, a 2021 OXFAM report revealed large-scale exploitation of immigrant workers in areas of Spain, Italy, France, Bulgaria, South America, New Zealand and South Africa, with issues ranging from excessive working hours, below-minimum wages and lack of insurance, to forced labour, abysmal housing conditions and severe health and safety hazards. International investigations even linked certain seasonal-labour agencies to organised crime groups involved in human trafficking.

But even in businesses where workers’ basic rights are fulfilled, improvements can be made. In its sustainable winery checklist, the US Pacific Northwest’s certification body LIVE states criteria for community impact, workers’ health, safety, education and benefits, from staff training and policy participation to adequate meal periods, rest breaks and availability of hygiene, sanitation and first-aid facilities. Remuneration for members must exceed legal minimum wages, with paid overtime and vacation, healthcare and retirement benefits. Equally, in South Africa, the IPW sustainability guidelines include staff training, health and safety measures.

Employability

Wineries can also launch own initiatives for a socially sustainable workplace. John Williams of Frog’s Leap in Rutherford, for example, invested in year-round employment and benefits for their immigrant workers. He involves employees in decision-making and continues to lower the spread between the lowest and highest-paid jobs. O’Neill Vintners & Distillers offer university scholarships and internships to advance the representation of black, indigenous and people of colour and ensure a well-rounded, diverse workforce. In 2011 Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton created a sheltered workshop for disabled employees, several of which secured permanent contracts at their Champagne houses since. In Bordeaux, Château Montrose developed ergonomic tools for its workers, while Château Anthonic increases employability by teaching vineyard skills to low-skilled young workers.

Community

Community

Social sustainability can also be improved by contributing to the local community, forging bonds with people, organisations and businesses in the region. Companies can recruit, source services or goods locally and support regional tourism and initiatives. When wine producers work constructively within their community, it raises the brand’s image and strengthens their employees’ positive feelings about the workplace. This in turn boosts employee retention, engagement, motivation, productivity and customer service.

Measures to mitigate negative impact on the community and enhancing environmental sustainability further improve employee relationships. As marketing expert Helen Wells asserts:

Better brand, happier staff. Being perceived as a green company is great for your brand image, and can make staff recruitment and retention easier. People want to work for companies that are part of the solution, rather than part of the problem.

Management

Finally, I want to stress the value of ‘enlightened management’ in employee relationships. For a business to be socially sustainable, it should not be run in fear, mistrust and micromanagement. Hiring the right persons for the job, rewarding them fairly, providing meaningful involvement and growth and training opportunities, are the ways forward. If this is actively and consistently put into practice, even staff who leave the business are likely to remain brand advocates. They can also become trusted contacts or business partners in their new capacity, which results in a strong, sustainable social network.

An example of a wine producer with such a strong socially-centred philosophy is Wirra Wirra in South Australia’s McLaren Vale. On their way to the entrance, staff and customers, referred to as the ‘Wirra Wirra tribe’, pass an installation with the words of the iconic Greg Trott, who revived the winery in the 1960s:

Never give misery an even break, nor bad wine a second sip.

You must be serious about quality, dedicated to your task in life, especially winemaking, but this should all be fun.

Continued in part 3.

This article is based on the July 2022 D6 paper Kristel submitted. Read it here.

Kristel passed this paper with distinction, a mark that few achieve for this unit within the WSET Diploma course.